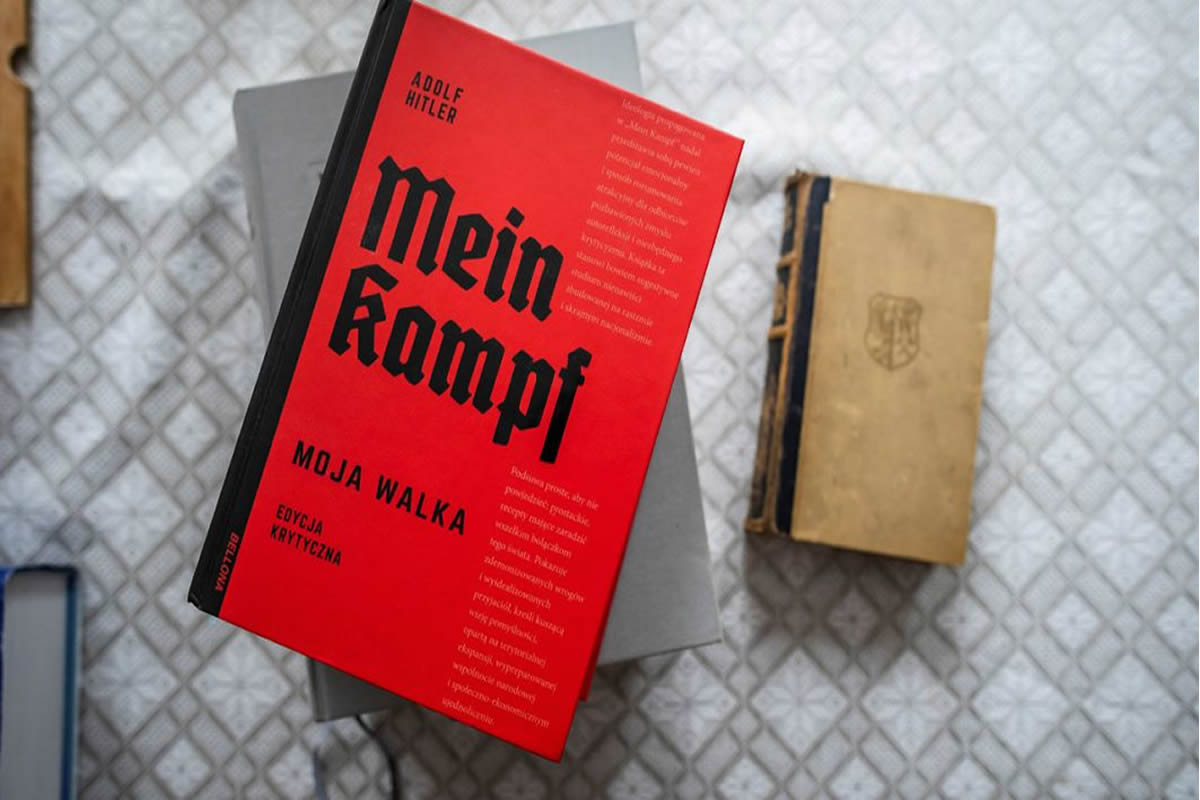

An academic edition of Adolf Hitler’s “Mein Kampf” is being published in Poland this week for the first time, with its editor responding to critics by calling it “a homage to the victims”.

Hitler’s inflammatory tract has rarely been published even after rights to the book, which first came out in 1925, entered the public domain in 2016.

“According to the critics, the publication of this book is an offence to the victims of Nazism. In my view, it is the opposite,” said Eugeniusz Krol, a historian who has been preparing the Polish-language edition for the past three years.

Pirate copies or abridged versions of Hitler’s blueprint for the rise of Nazism and the Holocaust have circulated in Poland for years.

In 2005, the government of Bavaria in Germany which held the rights at the time, requested the seizure of copies of one such version in Poland.

But Krol told AFP that this annotated Polish-language edition, which runs to 1,000 pages in total, would act as “a historical source in a wider context”.

The book, which will be published on Wednesday, will be only the second annotated edition of “Mein Kampf” — after a German one that came out in 2016.

Publication ‘a positive thing’?

The Polish edition is being handled by Bellona, a publishing house specialising in history books, and the first print run will be 3,000 copies.

The company will not be carrying out any publicity campaign for the book and the price of 150 zloty (33 euros, $40) is high for Poland.

“We do not want this publication to be widely accessible,” said Bellona’s director, Zbigniew Czerwinski.

He said the book was above all “a warning that it is easy to dismantle democracy and build a totalitarian regime in an almost invisible way”.

“What happened in Germany after 1933 can happen today, tomorrow, the day after tomorrow in many places in the world. The signals are easily understandable,” he said.

Piotr Cywinski, head of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum, said in the Rzeczpospolita daily that he could “understand” an edition of the book intended for academic purposes.

But he warned that any editor out to make money from the book who conducts an active publicity campaign “could come into conflict” with Polish laws against promoting fascism.

The public propagation of totalitarian ideologies like fascism or communism and ethnic or racial hatred is banned in Poland, a country that lost six million citizens — including three million with Jewish roots — under Nazi occupation.

The crime carries a penalty of up to two years behind bars.

Poland’s Chief Rabbi Michael Schudrich said an academic edition could be “a positive thing”.

It could “help people understand in a much more complete and profound way the dangers of Nazism, of lying, of totalitarianism,” he said.

He said the question of whether or not to publish the tract “was relevant 20 years ago” and it was important to understand that there was now a “consensus” of opposition to fascism.

Now “it is important that academics can read what Hitler wrote in ‘Mein Kampf’ because words count. And what Hitler said before coming to power was exactly what he did later,” he said.

Gistfox Your News Window To The World.

Gistfox Your News Window To The World.